From the moment an idea is born to its manifestation as a tangible creation, understanding the specifics of copyright protection is essential. And whether a work is published or unpublished greatly influences its copyright protection and associated rights.

In this post, we’ll explore copyright law as it applies to both published and unpublished works. By delving into the fundamental differences and similarities between these two categories, you can have a solid grasp of how copyright operates in each context and the implications for creators, consumers, and the broader creative community.

- Copyright protection is automatic upon the creation of a work, regardless of whether it is published or unpublished.

- Fair use provisions and other exceptions to copyright law apply to both published and unpublished works.

- While copyright registration is not mandatory for the protection of both published and unpublished works, it can offer valuable benefits and legal advantages for creators.

Table of Contents

Copyright Published vs Unpublished

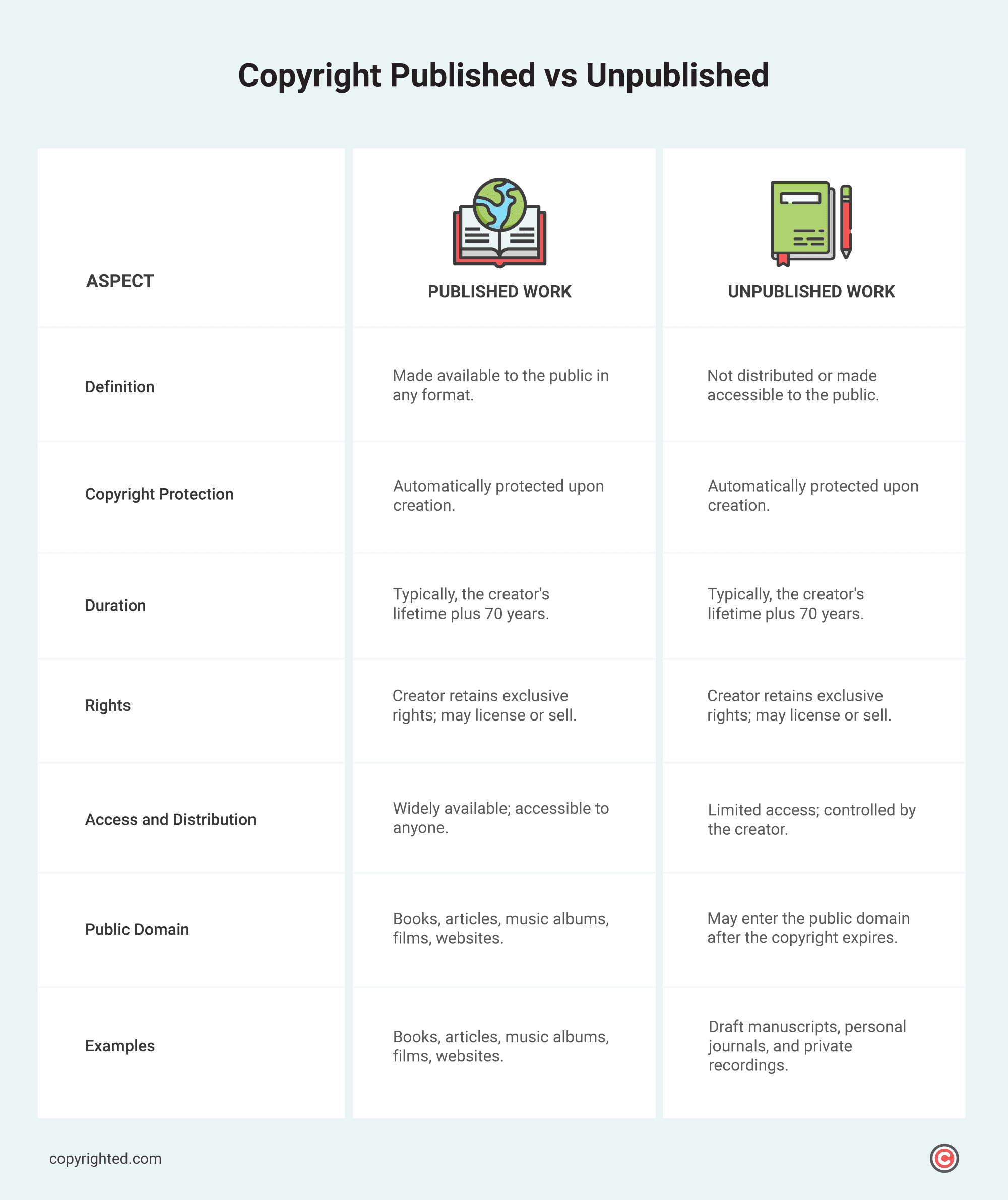

Whether a piece of work is published or unpublished can significantly impact its copyright status and the rights associated with it.

Published works, such as books, music albums, or films, have been made available to the public in various formats, ensuring broad accessibility. On the other hand, unpublished works, like draft manuscripts or personal journals, are kept private by the creator and are not distributed to the public.

Understanding these fundamental differences sets the stage for comprehending how copyright law operates in each scenario.

To provide a clear comparison, let’s break down the key differences and similarities between published and unpublished works:

How Does Copyright Apply to Published vs Unpublished Works?

Copyright protection serves as a cornerstone in the world of creative endeavors. However, the application of copyright differs between published and unpublished works.

Let’s delve into how copyright applies to each category.

Automatic Protection

Copyright protection is automatic upon the creation of a work, regardless of whether it is published or unpublished. As soon as a work is fixed in a tangible medium of expression — such as written down, recorded, or saved in a digital format — it is considered copyrighted.

This means that the creator holds exclusive rights to reproduce, distribute, perform, display, and create derivative works based on the original creation.

Unlike some other forms of intellectual property, such as patents or trademarks, copyright protection does not require registration with a government office. This automatic protection encourages creativity by ensuring that creators have the only right to benefit from their works without the need for formalities or bureaucratic processes.

Duration of Copyright

The duration of copyright protection is generally the same for both published and unpublished works. In most jurisdictions, copyright protection lasts for the duration of the life of the author plus 70 years.

Once this term expires, the work enters the public domain, where it can be freely used by anyone without permission or payment of royalties. The purpose of copyright duration is to balance the interests of creators in benefiting from their works with the public’s interest in accessing and building upon cultural and artistic works.

Exclusive Rights

Creators of both published and unpublished works hold exclusive rights over their creations. These rights include the right to reproduce the work in copies, distribute copies to the public, perform the work publicly, display the work publicly, and create derivative works based on the original.

These exclusive rights give creators control over how their works are used and allow them to benefit financially from their creations. However, creators can choose to license or transfer these rights to others, such as publishers, distributors, or licensors, through contracts or agreements.

Ownership

The initial owner of the copyright in a work is usually the creator or author. For published works, the creator may transfer or license their copyright to a publisher or another party as part of a publishing agreement.

In such cases, the publisher may have certain rights over the work, such as the exclusive right to publish, distribute, and sell copies of the work.

However, the creator typically retains certain rights, such as the right to be credited as the author and the right to receive royalties or other compensation.

For unpublished works, the creator generally retains sole ownership of the copyright unless they choose to transfer or license it to another party.

Fair Use and Exceptions

Fair use provisions and other exceptions to copyright law apply to both published and unpublished works. Fair use allows for the limited use of copyrighted material without permission from the copyright holder for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research.

The application of fair use depends on factors such as the purpose and character of the use, the nature of the copyrighted work, the amount and substantiality of the portion used, and the potential effect on the market for the original work.

Protection Against Infringement

Both published and unpublished works are protected against copyright infringement.

Copyright owners have the right to take legal action against infringers, which may include seeking injunctions to stop the infringing activity, monetary damages for lost profits or statutory damages, and in some cases, criminal penalties for willful infringement.

Enforcement of copyright protection helps to deter unauthorized use and ensures that creators can benefit from their works.

In summary, while the core principles of copyright protection apply to both published and unpublished works, being aware of the considerations specific to each category is still important.

Is Copyright Registration Necessary for the Protection of Both Published and Unpublished Works?

No, copyright registration is not necessary for the protection of both published and unpublished works. However, while registration is not required to establish copyright ownership, it can provide certain benefits and legal advantages for creators.

In many jurisdictions, including the United States, copyright protection is automatic upon the creation of a work. This means that as soon as a work is created — whether it’s written down, recorded, or saved in a digital format — it is protected by copyright law. This automatic protection applies to both published and unpublished works alike.

Despite this automatic protection, creators may choose to register their copyrights with the relevant government office, such as the United States Copyright Office. Copyright registration involves submitting an application and a fee, along with a copy or description of the work being registered.

While registration is not a prerequisite for copyright protection, it can offer several benefits:

- Prima Facie Evidence: Copyright registration provides prima facie evidence of the validity of the copyright and the facts stated in the registration certificate. This can be valuable if the creator needs to enforce their copyright in court, as it can simplify the burden of proof.

- Statutory Damages and Attorney’s Fees: In some jurisdictions, such as the United States, copyright registration is a prerequisite for pursuing statutory damages and attorneys’ fees in cases of copyright infringement. Statutory damages can provide compensation even if the copyright holder cannot prove actual monetary losses, while attorney’s fees can help offset the costs of legal proceedings.

- Access to Federal Courts: In the United States, copyright registration is also a prerequisite for filing a copyright infringement lawsuit in federal court. This can be advantageous as federal courts often offer more favorable remedies and jurisdiction over copyright cases.

- Public Record: Copyright registration creates a public record of the copyright claim, which can be useful for establishing ownership, conducting due diligence, and facilitating licensing or transfer of rights.

In conclusion, while copyright registration is not necessary for the protection of both published and unpublished works, it can offer valuable benefits and legal advantages for creators seeking to protect and enforce their copyrights.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can unpublished works be copyrighted?

Yes, unpublished works are eligible for copyright protection upon creation. This means that as soon as a work is created — whether it’s written down, recorded, or saved in a digital format — it is protected by copyright law, regardless of whether it is published or shared with the public.

Does publishing automatically strengthen copyright protection?

No, copyright protection is established upon creation, but publishing can provide additional evidence of ownership and help deter infringement.

What are the risks of publishing creative works?

Publishing creative works can expose them to potential copyright infringement, unauthorized use, and loss of control over distribution and adaptation.

What are the advantages of keeping works unpublished?

Keeping works unpublished allows creators to retain control over their distribution, maintain exclusivity, and avoid certain risks associated with public availability.

How does copyright duration differ for published and unpublished works?

Copyright duration typically begins upon creation and lasts for the creator’s lifetime plus an additional period, both for published and unpublished works. Once the copyright expires, the work enters the public domain.